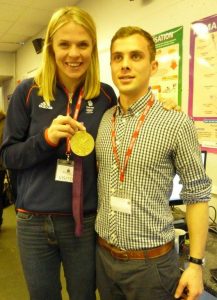

How is it possible for an 18 year old girl, just average at sport, not even particularly fit and never having been in a rowing boat, to be 11 years later part of Britain’s greatest Olympic success since 1908? As Anna Watkins herself admits, she had never thought about sport as a career until she found the one thing that she excelled at: rowing. Winning the Olympic gold medal in the double sculls in 2012 in London does not only illustrate the necessity of hard training and devotion. Anna Watkins’ career and success epitomize the UK’s long planned-for “Mission 2012”, supported by massive funding. With the following interview, SportSirene hopes to gain an insight into Britain’s and Anna Watkins’ success at the Olympic Games.

Anna Watkins, the global public perception of the London 2012 Olympic Games was enormous and the support of the British people was remarkable. The British athletes responded with world class results. To what extent did the support of the British audience help to push you to your limit and to win the gold medal?

I really think it made a difference. Normally, I see the last bit during a race as the worst one. But in the final race I don’t remember it being painful because the crowd was [so]loud and it felt [as if]we were rowing through the middle of the Olympic stadium. We felt the noise shaking the boat like a vibration! And the adrenaline during that race was so big. I really think that the crowd helped us crossing the line and made it easier to win the race. It was just amazing.

Did a general team spirit exist in the “Team GB”?

They did something really clever with Team GB. They took us to the cleverest workshop I ever experienced in my life. For instance, a presentation by Clive Woodward showed us the values of Team GB, like respect, to give us a sense what this Team GB is all about. They told us what sort of behaviour they expect from us and what we as professional athletes can expect from Team GB. The workshop really helped us to feel like “you’re one of Team GB”.

During the Olympic Games in Atlanta in 1996, Team GB won one single gold medal. The current Olympic success in London with 29 gold medals and third position in the medal table show the effectiveness of a long-term funding system, supported by millions of pounds. What kind of concrete activities and measures had been planned in advance of the Olympic Games? How did Great Britain increase its number of professional athletes?

[Britain spent a lot of thought on the] transition from amateur to professional level. GB realized that there were a lot of ex-athletes [who]had suffered from the lack of a national government scheme to help athletes through that transition. As a result, they set up [a number of]of individual charities that would give grants to athletes to help them fund the next step [to become successful elite/professional athletes]. [In my case, after my] victory in the U23 World Championships I was supported by National Lottery funding.

[In advance of the Olympic Games], we received a broad range of sports science support: full-time physiologists, [the ability to do]all of our training sessions at the rowing machine with lactate testing to get a massive database on how your lactate levels are composed. We do that on the water as well. [We also worked with] sensor techniques on the rowing machine in biomechanical labs to analyze our peak power, etc. or the strain gadgets in the boat. [And] we work with the best nutritionist in the world concerning athletic nutrition. We go through food diaries, control the proteins, etc.

To what extent can sporting excellence be achieved through national funding in your opinion?

There is a lot you can do I guess in essence if you are prepared to have a funding programme that attracts the best people that is going to have an impact. I know that in rowing in the UK the focus is on schools and university programmes that act as a successful feeder into national squads. People who run the [athletics]organizations [face]problems like “how is sport in schools?” and whether the athletes are coming through to the programmes. People [are]the main resource, that’s important. [But] the funding in Britain is controversial because they give it almost entirely to the sports that are doing well. As a professional athlete you get a grant dependent on your success, so you have a small grant if you compete, then a better grant if you are in the top six and a top grant if you win a medal. And the next year if you don’t achieve the same success your grant drops. I think that’s why we are doing well because the money goes to where success is. And [that]means those sports have a momentum but it is difficult for new sports to break in.

You beat the Olympic record, and therefore your personal best, with your rowing partner Katherine Grainger during the semi-finals in London. However, to focus on rowing as a very training-intensive discipline, how important was it during the preparation stage to excel and to push yourself to your limit over and over again?

It was really important that I had to learn that going to the max isn’t the best way to train. I’ve had to learn to know my body and how to pace myself through the training programme, not just through the race. But it was really, really important to me to go into the Olympics having done a dress rehearsal which was absolutely [our]maximum, the best that we could do. We [had]a race against the rest of our training team in Italy two weeks in advance of the Olympics. That was the best race we ever did. It was terrific and we beat the world record in private.

The success of winning an Olympic medal comes with appreciation, attention and numerous congratulations. You appeared for example several times on BBC Newsnight, a show comparable to the German tagesthemen. Is there any negative side to the success?

I found it disconcerting to be suddenly treated differently. A lot of the celebrity stuff is weird and a superficial world. It’s fun because you go on the red carpet and you meet famous people. But it is just not real. Everybody is just trying to be more famous than everybody else is. It was quite an education how the media world works. I am happiest when I am around sports and talking to people [who know]what it is really about and that is not about fame. I’m glad that I’m not in that world all the time. Yeah, the celebrity stuff; I’m glad that I’m not in that all the time.

Sebastian Graf (Leek, den 23. November 2012)

- „Alles ins Gold!“ – Bogenschießturnier beim SV Derendingen ein voller Erfolg - 3. Juni 2014

- Die unbezahlten Profis? - 31. Januar 2014

- Racketlon – König der Rückschlagspiele - 16. August 2013